Welcome to the Weekend Reccs. This newsletter delivers a lovingly-tailored collection of thought-provoking goodness for your Sunday. Inside you’ll find: (1) a weekly column on economics, politics, or something unexpected, (2) a curated list of links for your enjoyment, (3) a lagniappe (because everyone deserves lagniappe), and (4) a collection of interesting, relevant charts. Grab a coffee and enjoy your morning.

New here? Be sure to subscribe to never miss an issue and please share a post with your friends. This newsletter relies on word-of-mouth!

The links marked with asterisks (*) are the recommended reads.

Hi friends,

Happy Sunday. Hard to believe it is time for Festivus and Christmas already. Read to the end for my Christmas wish.

Find below the third installment of Vaccinating Against Bad Economics. Jump past this section to get to this week’s recommendations.

The Long Read: VABE 3, “We have to prioritize the national debt.”

This is one of my favorite topics.

We will hear Mitch McConnell say over and over again in 2021 that we cannot afford X, Y, or Z expenditure, or that we need to “get our fiscal house in order” or something similar. This is not accurate.

Today, I’ll discuss a few incorrect ways folks think about the federal government’s budget, and propose a framework that suggests that we can, and should, spend a lot of money to get out of this recession.

As this is, and forever will be, a general audience newsletter, I’ll do my best to avoid (or explain) jargon, and keep focus on the big picture. This sometimes requires a loss of nuance. To the degree this is detrimental, let me know! Figuring out how to make complex things accessible is a difficult thing and I can’t get better at it without getting feedback.

If you are not convinced that there is a need for extra stimulus, I suggest starting here.

Additionally, I’ll use the phrases “monetary policy” and “fiscal policy” a lot. The prior, for the most part, refers to altering the money supply (the number of dollars) in the economy through changing interest rates. The latter is about altering both government spending and taxation.

It is incorrect to say the government needs to behave like a household

The greatest sin when talking about fiscal policy is to make reference to how a household could never run this way, or how, if the federal government were a household, it would be “charging the credit card despite being in debt” (to paraphrase the Heritage Foundation).

To put it bluntly, the federal government does not need to save like a household because while people are temporary, the federal government is eternal.

One day, you will no longer be able to bring in income through your labor. In order to prepare for this eventuality, you’ll need to save money either to spend when you don’t have an income or to produce an alternative income stream. To this end, you’ll want to pay down your debts.

The federal government does not suffer senescence. It can collect taxes no matter what its age is. That is to say, its cash flows have an infinite time horizon. It does not have a direct need to ever discharge (pay off) its debts, it just needs to find a new lender and roll the principal over into new debt. It does have to pay interest on its debt, and there may be a time where it makes sense to pay off the principal to manage this interest. However the principal does not need to be paid off for its own sake.

There will always be a market for US government bonds. If things go catastrophically poorly that market may charge exorbitantly high interest rates, but there will always be a way to roll the debt over.

It is incorrect to say that the government does not need to worry about the debt at all

One can certainly overcorrect here. Some would go so far as to say that the US does not actually even have to worry about the debt or its interest at all since it can print its own money, and so the only real constraint is inflation. (Inflation arises here because the new printed money makes older money less valuable since there are now more dollars for the same goods and services.) This is, more or less, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). While it could be the case that MMT is theoretically true, it is not a useful framework in practice.

There are a few reasons for this. The most pertinent is that Congress moves incredibly slowly. For MMT to hold, we would require all the following to be actively responsive to the economy’s health: (1) expansionary monetary channels, (2) contractionary monetary channels, (3) expansionary fiscal channels, (4) contractionary fiscal channels.

The first and second are covered by the Federal Reserve.

The third sometimes happens nimbly, as we saw with Congress passing the CARES Act.

The fourth, however, requires tax hikes or spending cuts, which we have little evidence any Congress would be willing or able to do nimbly. The problem here is that if you’re in an ultra-high-debt, high-inflation world, and then can’t cool down the economy (use contractionary fiscal channels), this whole worldview collapses.

The monetary tools would now be faced with either (1) keeping rates steady and letting inflation ride at high levels (which can be economically disastrous) or (2) raising rates, which increases the costs associated with the already high levels of debt, which now therefore requires more inflation to cover, which requires higher rates, and so on it spirals.

The implication, then, is that because fiscal channels cannot be expected to be reactive to changing dynamics, we must be thoughtful across longer time horizons. Congress is so slow to the draw that it is possible for us to have inflationary meltdowns that can’t be stopped if we don’t recognize some fiscal limitation.

So maybe Modern Monetary Theory would be accurate in a perfect world. But we are not so lucky. We have been struggling for months to get very popular fiscal stimulus passed through Congress. Why would tax hikes be more possible?

With this in mind, we should therefore recognize there is a real and significant interplay between monetary and fiscal policy, but we should not expect one to be able to come to the rescue of the other.

Interest payment management as a balanced approach

We’ve seen the government is not a household because it can roll over its debt forever.

We’ve seen the government is not able to ignore the debt levels altogether because Congress is not nimble enough to raise taxes or slash spending if necessary.

In between these two is a fiscal policy framework centered on management of interest payments.

Because the debt can be rolled over, the only bills that come to the US Treasury that matter are interest payments on the federal debt. Spending can be packaged into debt, debt can be rolled over to more debt, and so the only thing that the US ever really pays for is interest on the debt.[1] That is to say, interest rates are the cost of holding debt.

Think about it this way. Let’s pretend the government pays only $1 interest per year, and can expect to pay $1 in interest in the future. Knowing that, would it matter that the debt level is $8 Sextillion or $8 Trillion or $8 Billion or just $8? No. Because that debt will be rolled over into future bonds, and we said at the outset they will have a rate such that the interest payment will be $1. The level of debt only matters in so far as it alters the interest being paid.

If we were instead to say the government faces 1% interest on the debt, then we’re talking about a difference between $8T, $8B, $8M, and $.08 in interest payments per year. That difference does matter, but only insofar as it changes the interest due.

And so given that we can roll over whatever level of debt we hold, looking at the debt-to-GDP ratio (as everyone does) is nonsensical.

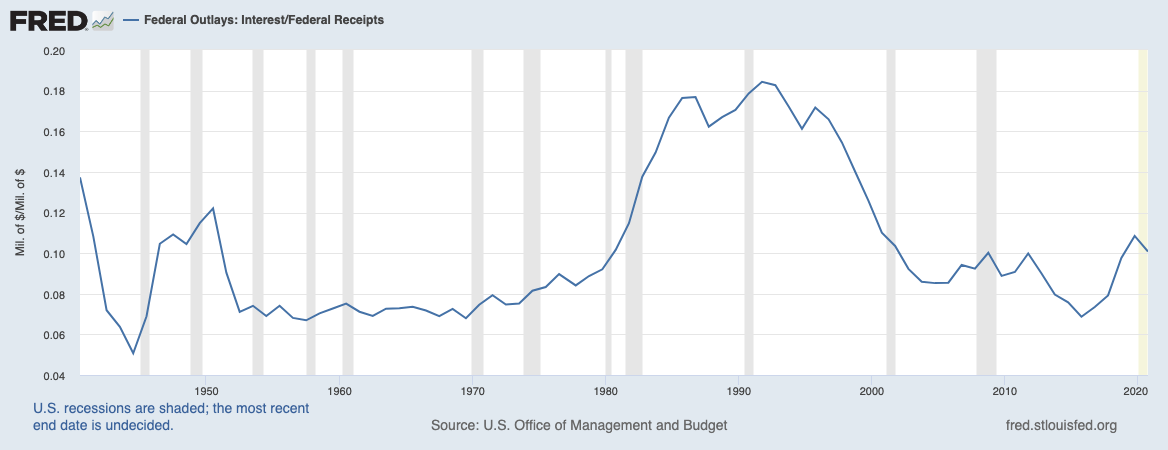

In the real world, we use federal receipts (basically, tax revenues) to pay off interest.[2] So let’s stop of talking about how the US debt is 127% of US GDP and start talking about how interest payments on the debt are only 10% of federal receipts.

The current situation

To be clear from the outset, the percentage where we should start thinking about austerity is almost certainly less than interest/receipts reaching 100%. However, how far away it is from 100% is not what I want to focus on.

Instead let’s focus on today.

As of September 30, 2020 we were at 10% and going down as we rolled new debt into lower interest bonds. That’s right, despite the trillions in spending this spring we went down because of low interest rates.

What’s more we’ve reached 18% in the past without problems whatsoever. No run on Treasuries. No catastrophic meltdown due to loose money. No runaway inflation. None of the nonsense you’ll hear next year.

Getting to 18% today would look like trillions more dollars in stimulus since interest rates are so low. And that is without any changes or increases in taxes once the economy is once again running hot.

What about the long term?

Things look a lot different if we’re talking about spending trillions more every year. But we’re not, we’re talking about a one- or two-time event.

So let’s look at what taking on $1T of debt today in 30 years bonds would look like.

Thirty-year Treasury notes are currently trading at 1.7%.

Inflation is expected at 2% per year. CBO projects we’ll have 2% real GDP growth per year going forward. This means we can assume for any given year the nominal GDP (and therefore tax revenues) will grow ~4%. So we’ve got 4% growth on our revenues and are paying out 1.7% interest, that means we’re looking at the $1T shrinking by 2.3% each year relative to federal revenues.[3]

So rolling over that $1T in 2050 will be as impactful as $498B today (that’s the magic of compounding!). That’s right, without doing anything but running the economy normally we diluted more than half of the debt through economic growth and stable inflation. This what folks mean when they talk about growing out of debt.

Adding $1T at 1.7% would add $17B per year to our interest. Looking back at our interest/receipts, this would move us from 10% to 10.5%. Adding $5T would get us to 12.5%.

The best part? That $1T (or however much) doesn’t go into thin air. The whole reason we’re talking about this is that we’re talking about supporting the economy and increasing economic growth. By being smart with its allocation, perhaps dolling out a large chunk to those hurting most and spending the rest perhaps investing in our children’s economic futures, or our crumbling infrastructure, or basic science, or helping support entrepreneurs, we possibly could exceed that 2% growth and dilute the debt even more.

We’re not mortgaging our kid’s futures, we’re setting them up for success by taking a sweetheart deal.

What about the fact we run a deficit each year?

Walking through the numbers on deficit projections and interest rate projections gets lengthy quickly. To be concise and keep this accessible, the deficit is pretty small in terms of how much it adds in terms of interest in both our current very low interest rate environment and when we take into account future expected rates. Additionally, taxes will go up without legislative action due to a “poison pill” provision in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (Trump Tax Cuts) that is set to raise taxes in 2021.

The small addition of interest attributable to these deficits means there is plenty of time to address them during economic booms, and that they don’t matter at all in cases where we’ll grow out of them. We don’t need to be handling them in the middle of a bad recession.

Lastly, we face some risk from rising interest rates. But long-term projections of interest rates are still quite mild and suggest we can spend a lot today. Further, the more long-duration bonds we use, the less risk we face from interest rate rises. This is why I believe we should bring back consols, which are bonds that never mature (that is, they pay interest forever).

The federal government is also not a business

All this talk about bonds and fiscal prudence can get us a little tunnel-visioned. It would be misguided to think we should focus only on government spending that will maximize future growth.

The federal government is not, and should never be, trying only to maximize future revenues. In America, at least, we think the federal government has a lot of other things it should focus on, like establishing justice, ensuring domestic tranquility, providing for the common defense, promoting the general welfare, and securing the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity. The point here being it is ok to spend that $1T+ on things we think are important that aren’t strictly tax-revenue maximizing, like a pivot to carbon neutrality. The federal government’s objective function has a lot of components, and investing in future growth is an important component, but it is only one of them.

Takeaways

The federal government is not a household. Its cash flows will continue forever. We therefore do not need to discharge our debt for any reason other than if we are worried we will be unable to cover the interest payments in the future.

We do not have a nimble mechanism for employing contractionary fiscal policy (e.g. tax hikes and spending cuts). As such we cannot, and should not, spend as though there is no fiscal constraint whatsoever. But again, for today, we are wholly safe to spend at least several trillion more than we have to address this crisis (and the climate crisis, while we’re at it — green jobs are real jobs that pay real wages and support real families).

Debt/GDP does not mean anything if you never intend to pay off the debt. We instead should talk about Federal Outlays for Interest / Federal Receipts. This ratio, between the costs of holding debt and the amount of money we can spend to cover the debt, is where the true action happens.

We see in the numbers that we can, and should, spend an amount of money that most people find unfathomable to support the economy and accelerate our path to full employment.

We can afford to do more to stabilize the economy, invest in our children, repair our infrastructure, support the elderly and disabled, fight climate change, and provide relief to those feeling acute hardship. Congress and the President need to take bold action. It is not just the right thing to do, it’s the smart thing, too.

A big thanks to Benedict Brady and Connor Murphy who have continually refined my views on this topic through many discussions and arguments.

The Links

O holy night! The stars are brightly shining* Tomorrow, the conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter will create a super bright object in the sky that some are calling a “Christmas Star.” Lay astronomy is like sports broadcasting in that everything is a big deal (“The closest Mars will be to the Moon in 500 years!” = “Well, Dale, this would be big news, it would be the third home game on a Tuesday where Smith has pitched a no-hitter.”)…but tomorrow’s conjunction has the makings of a very special phenomenon to witness; you won’t want to miss it.

Spirit-ual* How the peculiar monks that make the liqueur Chartreuse are faring amid the COVID pandemic (s/o Aren Rendell).

Ten Meter Tower* This short film is exceptionally good (s/o Kaylyn Tuggle).

Oreo keeps releasing new flavors because new flavors increase original flavor sales*

Cuddleup: (noun) a casual encounter* This is one of many words invented by Thomas Dimson’s This Word Does Not Exist. I spent longer than I would like to admit refreshing the page.

Lagniappe

With the end of the year in sight, I thought I’d offer a reflective suggestion.

I keep a running list of several books, articles, etc. that I wish to revisit. I think of it as a once-every-three-years list, though many items I revisit more often. It is nothing elaborate, just a note on my phone.

Every so often I’ll check it and see if I’ve forgotten what was special or important about the items on there, and if I’ve forgotten I’ll pick that thing back up. Give it a try. You’ll be surprised how many things you want to keep coming back to, and how grateful you will be when you do.

Graph(s) of the week

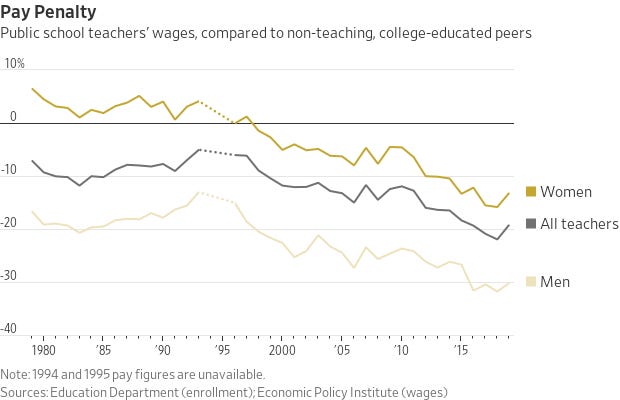

[WSJ] Everybody talks about how “throwing money at the education problem doesn’t work,” but it seems to me we haven’t really tried throwing money at the idea that being a teacher is a challenging and thankless job…

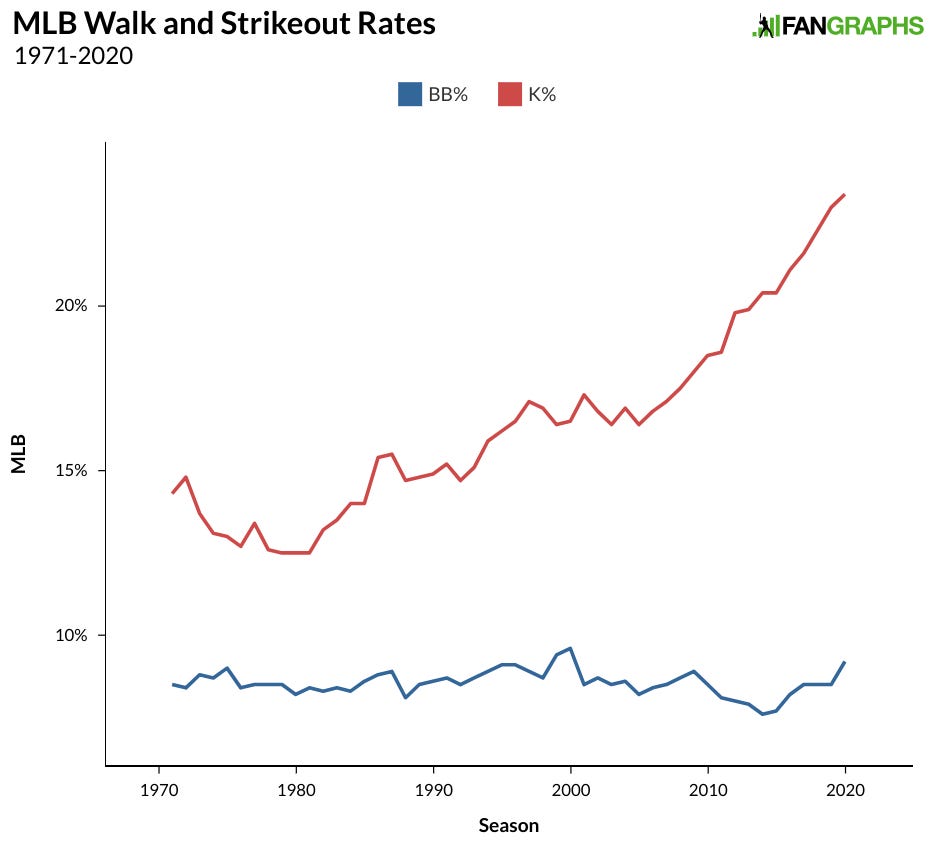

[Fangraphs] One of the reasons baseball seems so boring? Pitchers have gotten too good; one at-bat out of every four results in a strikeout.

🎁About that Christmas wish…

This newsletter takes me anywhere between 5 and 20 hours each week to pull together. I do it because I really enjoy it, and because so many of you have told me how much you love reading it. That being said, it only grows by word-of-mouth. So, if this issue, or any issue, has made you think or smile, please click the present to share that goodness with someone. Or, to put it lyrically:

🎶Make my wish come true,

All I want for Christmas is you (to share this post of the Weekend Reccs on social media and/or forward it to 5 of your friends).🎶

Thankful for y’all.

Happy Holidays,

Harrison

Footnotes

[1] Astute readers may at this time be asking why we don’t package interest payments into the debt as well. Functionally that may happen inside the US Treasury computers, and revenues may go to discharge other debts, but the point here is about the flow of revenues and expenses, not about the actual mechanics of tracking each dollar. As far as why it would be a bad thing if the cost of interest exceeded revenues, readers should recognize this would create an exponentially growing interest payment and refer to the second section above. Effectively, the interest payments are our cost for holding the debt, and our revenues are our way of covering that cost. The debt gets unsustainable when we either directly cannot cover that cost, or when expected changes in interest rates suggest we will soon no longer be able to cover that cost. We are not nowhere near either.

[2] See footnote [1]. Again, even if not the flow of things in actuality, we can sustain any level of debt so long as we can cover the interest.

[3] NB: This exact number won’t happen in real life, as inflation and growth fluctuates when things like global pandemics happen, but the point I’m trying to make here doesn’t require super precise numbers. We all can see that 4 is a lot larger than 1.7 and that matters over a 30-year time horizon.

I would like to note that in addition to Benedict and Connor I have continually supported your instinct that there is something about MMT that can't be quite right. "Support > rigorous take quality refinement" (source: https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/constitution-transcript). Never forget.